News

HMS Is Facing a Deficit. Under Trump, Some Fear It May Get Worse.

News

Cambridge Police Respond to Three Armed Robberies Over Holiday Weekend

News

What’s Next for Harvard’s Legacy of Slavery Initiative?

News

MassDOT Adds Unpopular Train Layover to Allston I-90 Project in Sudden Reversal

News

Denied Winter Campus Housing, International Students Scramble to Find Alternative Options

In the Red?

As the Class of 1953 entered its senior spring, the McCarthyist probe zeroed in on Harvard, “the Kremlin on the Charles.”

When Alan L. Lefkowitz ’53 arrived at his Navy base soon after graduation, instead of the hearty welcome he expected, he says his fellow officers eyed him suspiciously—thinking that because he hailed from Cambridge he must have communist ties.

“[They] looked askance at me because I had gone to Harvard,” he says.

By 1953, Harvard had come to be known as the Kremlin on the Charles. Letters to The Crimson accused the University of being a center of communist indoctrination. Sensationalist headlines in major newspapers and small-town dailies lambasted Harvard for harboring “Red” faculty members.

In a time when Cold War tensions were approaching their pinnacle and Sen. Joseph McCarthy, R-Wis., had initiated a vigilant effort to weed out communist sympathizers from every crevice of society, a degree from the nation’s oldest university was cause for extra suspicion.

“‘Our American schools’ were hotbeds of Communist infiltration, it was claimed,” the Class of 1953 yearbook editors wrote in a retrospective of their senior year. “And, as usual, Harvard was among the hottest beds.”

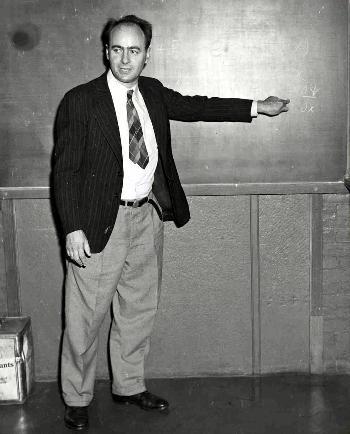

The fear of Harvard as a communist threat was played out on the national stage in the spring of 1953 when Congress interrogated Harvard physics professor Wendell H. Furry about his alleged communist associations.

The investigation—which extended to two other Harvard faculty members—became the landmark case for government attempts to root out subversion in American education.

While McCarthy cast a critical eye on many universities, he focused most intensely on Harvard, determined to root out communists hiding in the woodwork.

And to make matters worse, in June 1953 the Harvard Corporation tapped Nathan M. Pusey ’28—an old opponent of McCarthy’s—to be the new University president. Immediately, McCarthy started a very public war of words, warning American parents to keep their children out of the clutch of Harvard communists.

The members of the Class of 1953 may have been part of the so-called “Silent Generation” that eschewed political activism, but watching their professors on trial for their jobs would leave a lasting mark on their senior spring.

Hunting for Campus Communists

Lefkowitz and his classmates came to Cambridge as fears of communists at home and abroad were mounting toward hysteria.

The Soviet Union was known to have the atomic bomb and in 1949, the Communist Party was victorious in China. Communist North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950, setting off a war that the United States soon entered.

Earlier that same year, Harvard Law School graduate Alger Hiss was sentenced to prison for almost four years after lying under oath about his associations with Whittaker Chambers, a former Communist.

And in February, McCarthy, then an unknown senator from Wisconsin, told a group of people at the Wheeling, W.Va. Women’s Club that he had a list of 205 communists in the State Department—and was planning to root them out.

“Things were kind of hairy in connection with East-West affairs,” Walter F. Greeley ’53 recalls. “McCarthy started waving his supposed evidence about this and that...People started by taking McCarthy somewhat at face value.”

Nationwide attention turned to colleges and universities as well. Many states, including Massachusetts, instituted loyalty oaths for teachers, in which faculty swore to defend and protect the U.S. Constitution. State Rep. Paul A. McCarthy, D-Somerville, and Superior Court Clerk Thomas Dorgan proposed a series of bills geared toward limiting the perceived threat of communists on campuses, including one in 1950 calling for the removal of communist teachers.

And after the 1952 congressional elections, Rep. Harold Velde, R-Ill., chair of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and Sen. William Jenner, R-Ind., chair of the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, announced an investigation into the feared communist influence within educational institutions.

In his presidential report at the outset of 1953, University President James B. Conant ’14 announced his ambiguous stance on the probe.

“There are no known communists on the Harvard staff,” Conant said, adding that he hoped that the government would “ferret out” communists devoted to subversive activity. He would not support the appointment of a communist adherent in any educational environment, he said.

At the same time, Conant said he feared that the congressional investigation of faculty members would create an oppressive atmosphere at the University that would quash its academic freedom.

“The independence of each college and university would be threatened if governmental agencies of any sort started inquiries into the nature of the instruction that was given,” he told the Harvard community.

Harvard’s student body appeared to support his gesture.

In March, the Student Council urged the University to continue teaching about communism from an objective academic standpoint. Congressional investigation could “stifle free thought through the pressures engendered by widespread fear,” the council warned.

But some wondered whether students were entirely immune to the Red Scare mentality.

Associate Professor of History Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. ’38 criticized students for cancelling an appearance by a left-wing novelist and screening a movie starring an actor rumored to have communist ties.

“It is a stirring commentary on the courage of this new generation that the faculties and governing bodies of a university should be more in favor of free speech than the students,” Schlesinger wrote in an April letter to The Crimson.

Student organizers said that the cancellations had not been the result of political concerns.

But Schlesinger’s barb stung nonetheless—an indication that tempers ran short in the charged spring of 1953.

As the congressional focus on combatting communism in universities crescendoed, Harvard students, faculty members and administrators were increasingly forced to decide where their loyalties would fall.

Washington Targets Harvard

That spring, the mounting pressure on academic institutions to root out communists in their ranks came to a head at Harvard, when three members of the Harvard faculty became targets of a McCarthyist investigation.

In February and again in April, Congress demanded that Associate Professor of Physics Wendell H. Furry appear before Velde’s committee to face questions about his ties to the Communist Party during his time as a research associate at MIT.

Furry denied that he was currently a communist, but when pressed about his past associations, invoked his Fifth Amendment rights to withold information.

The other two faculty members, Assistant Professor of Anatomy Helen Deane Markham and Social Relations teaching fellow Leon Kamin, maintained similar silence under congressional scrutiny.

Facing pressure from Washington, the Corporation decided to review the employment of the three faculty members in light of their unwillingness to answer all questions in the national inquiry.

At other universities, taking the Fifth was considered an admission of guilt and grounds for dismissal, and earlier in February, Conant had indicated that Harvard would follow a similar policy.

But the Corporation’s final decision did not uphold this stance.

In a move that shocked and affronted ardent anti-communists, the Corporation announced on May 19 that it would retain all three members on the Faculty. Furry and Kamin, their report concluded, were no longer members of the Communist Party; Markham had never been a member.

While the Corporation reprimanded Furry and Kamin for their past communist associations and condemned the invocation of the Fifth, they allowed the three faculty members to keep their positions at Harvard, a move that most of their Harvard colleagues applauded.

“Virtually every professor contacted yesterday called the decision ‘courageous’ and ‘wise,’” The Crimson reported on May 22.

Activities, Not Activism

While the shadow of McCarthyism hung over the entire University and members of the Class of 1953 say they were aware of the suspicions surrounding several faculty members, there was more discussion than political activism among students at the time.

“There was constant discussion of the degree to which professors might or might not be sympathizers,” says Greeley. “There were a lot of professors who were very, very liberal but certainly not communists, yet at the time there was the danger of classing them a little bit on the pink side.”

Alan G. Gass ’53 says he noticed tensions mounting during his last two years at Harvard.

“At the beginning, everyone thought McCarthy was a joke,” he says. “It turned out he was as evil as he could have been.”

The Crimson published special reports on academic freedom and wrote editorials in support of Furry’s refusal to testify.

“The Crimson was at the forefront of the fight against McCarthyism,” says then-Crimson President Philip M. Cronin ’53.

But several students say they and their classmates were too caught up in college life to focus on national events.

“I think everybody intellectually was very upset with McCarthy,” says Guido R. Perera Jr. ’53. “[But] there was very little direct impact on us....McCarthy could have been doing any number of things on a day-to-day basis. It didn’t mean anything at Harvard.”

Robert L. Consolini ’53-’56 says he was too busy learning new things and exploring Harvard’s cultural resources to worry about McCarthy.

“Harvard was just one cornucopia of opportunity and excitement,” he says. “And being involved in national politics? It was just not germane to the options that were just in front of us all the time.”

Even though several political organizations existed on campus at the time, including the Young Republican Club and the Young Democratic Club, members of the class say they don’t recall any major demonstrations like those that occurred on college campuses during the Vietnam War era.

The Liberal Union, a student chapter of Americans for Democratic Action, had almost 300 members, but the Young Progressives had difficulty simply recruiting the 25 members they needed to be an official student group.

“You have political activists in every class,” says Greeley. “The question is how many other people get swept along with them. In our class not too many people got swept along with it.”

‘Pusey vs. McCarthy’

The aggressive probe of Furry was just the beginning of a long battle between Harvard and the fervent anti-communists in Washington.

For a year after members of the Class of 1953 left Harvard with their degrees, McCarthy continued to search for the elusive Reds within the Yard walls.

His focus on Harvard only intensified in June when Pusey, the young president of Lawrence College, replaced Conant as University president.

Pusey hailed from Appleton, Wis., McCarthy’s hometown. The two had crossed paths just a year before when Pusey was one of 100 prominent Wisconsin residents who signed a booklet, titled “The McCarthy Record,” that criticized the senator’s political decisions during his reelection campaign.

Cronin says the Corporation’s choice of Pusey made a clear statement in the tense climate of the 1950s.

“His very selection indicated strong support of somebody who was very anti-McCarthy,” he says.

Soon after the decision was announced, McCarthy issued a harsh public statement against Pusey, telling the Boston Traveler in a letter that the new president’s political stance was “a combination of bigotry and intolerance behind a cloak of of phony hypocritical liberalism” and calling him a “rabid anti anti-Communist.”

At least McCarthy was happy to have Pusey out of Appleton.

“Regardless of who takes his place [at Lawrence College], it will be an improvement,” he said. “In other words, Harvard’s loss is Wisconsin’s gain.”

Yet again, Harvard was the university at the forefront of the Red Scare.

Small-town newspapers throughout the country printed excerpts of McCarthy’s letter within 48 hours of its release, dubbing the attack “Pusey vs. McCarthy.” A torrent of editorial letters flooded publications’ mailboxes.

The July 8 issue of the St. Albans Messenger declared, “Pro-Communism is rife in American education,” but Pusey himself had few words for the press.

“When McCarthy’s remarks about me are translated it means only—I didn’t vote for him,” he told the Associated Press.

Red Harvard?

In his first months as president of Harvard, Pusey acted as the stubborn “anti anti-Communist” that McCarthy had labeled him.

McCarthy was not ready to let Furry off the hook, but Pusey defied pressure to fire the professor.

“I cannot conceive of anyone sending their children anywhere where they might be open to indoctrination by Communist professors,” McCarthy told the Boston American in November 1953.

Pusey simply responded to McCarthy at a press conference by restating Harvard’s opposition to communism—but with the caveat that the University “is dedicated to free inquiry by free men.”

A year after his investigation, Furry finally disclosed the extent of his associations with the Communist Party. He became involved, he said, in 1938, attending a series of informal discussion groups in Cambridge.

“Often, we would plow through a few pages of some ‘classic’ we were studying,” he told The Crimson in February 1954. “What I knew of [the Communist Party] years ago was limited to a small group. So far as this group was concerned, I believe that membershp in the Party at that time was quite consistent with being a loyal American.”

Furry said that in 1946 he noticed an anti-American trend in Party literature and by the following year had severed his ties with the group.

Despite this qualification, Furry’s past made him one of the most visible targets of the anti-communist crusade and Harvard a symbol of the supposed Red infiltration of American academia.

In 1956, the Corporation would investigate five more faculty members with possible communist ties.

But 1953 would go down as the height of the Red Scare at Harvard, when Washington tested academic freedom and the University rebelled.

The McCarthyist investigations—and the waves of suspicion that followed—set the tone for a generation that, politically active or not, could not escape the fear that spread all the way to the University’s hallowed halls.

“Politics and international relations were very to the forefront of what was going on daily at Harvard and in our class,” says Greeley. “It was not a quiet, dull time by any means.”

—Staff writer Nathan J. Heller can be reached at heller@fas.harvard.edu.

—Staff writer Jessica R. Rubin-Wills can be reached at rubinwil@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.