News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

Self-Righteous Liberals at 19

A specter is haunting American colleges—the specter of conservatism.

As readers learned from last Wednesday’s comment, more college students are identifying with conservative policies. On May 25, 2003, the New York Times Magazine reported this trend on campuses nationwide: “Today’s surge reflects a renewed shift pronouncedly to the right on many defining issues.”

There is little evidence that the “renewed shift” is going on here. Instead, Harvard liberals accuse conservatives of stuff like “worldly concerns” and “fretting about the economy at the expense of abortion rights.” The resurgence of campus conservatism is attributed to students “thinking less like activists and more like conservative CEOs.” In an op-ed last spring, a Kennedy School of Government (KSG) student accused commencement speaker and Massachusetts Governor W. Mitt Romney of “putting self above the common good” and deviously crafting “a good political message” without “letting something simple as the truth get in the way.” With no sense of irony, the student then suggested that KSG choose instead as commencement speaker “a token Republican to prove its liberal reputation is undeserved.”

Clearly then, KSG isn’t above political concerns, nor should it be. Self-interested behavior like working for profit and political posturing characterizes not just conservatives, but everyone. One readily observes that political parties, whether conservative or liberal, propose strategies in order to enhance their power and solicit campaign contributions in order to get their candidates elected.

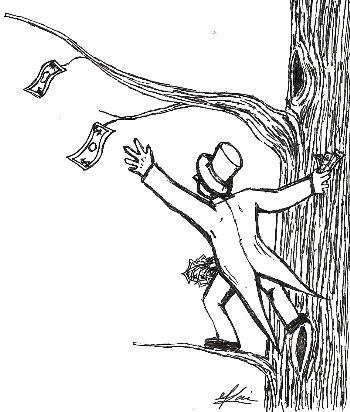

Self-interest motivates most human behavior, and therefore, it’s peculiar that liberal students would choose it as a target for their indignation. It’s even more peculiar, considering Adam Smith’s philosophy in The Wealth of Nations: “By pursuing his own interest [an individual] frequently promotes that [interest] of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good.” The “public good” that students “thinking like activists” purport to advocate, while sneering at their classmates’ pettily provincial ambitions, is best achieved by means of self-interest. Activists trumpet the best outcome for humanity and curse the common people who realize it, all in the same breath.

The irony of it all is lost at Harvard. Saucy diatribes against investment bankers, flat-tax advocates, and politicians working in the private sector would be comical for their simplicity, if they didn’t attack so viciously many students’ noble visions of what it means to be successful in life. A student dreaming of becoming a CEO, for example, finds fulfillment in the quest for wealth (see Adam Smith on the nobility of such a motive).

Maybe students with fewer “worldly concerns” recoil in horror at the thought of making money. But the universal nature of self-interest suggests that the CEO and the liberal activist are fundamentally the same: The activist finds his own fulfillment in activism and the manipulation of power structures that accompanies it. (Remember that, in social movements, there is always a demagogue who stands to gain. “Hasta la victoria siempre!”) As the quest for wealth is no more self-interested or self-gratifying than is the quest for power, Harvard’s budding businessmen, investment bankers, and CEOs do not deserve to be singled out for browbeating and moral outrage.

Meanwhile, at other schools, there is still the specter of conservatism. The specter looms, not because students of this generation are more selfish, but because they are unwilling to support a moral hierarchy that devalues their own blameless aspirations.

—Luke Smith is an editorial editor.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.