News

When Professors Speak Out, Some Students Stay Quiet. Can Harvard Keep Everyone Talking?

News

Allston Residents, Elected Officials Ask for More Benefits from Harvard’s 10-Year Plan

News

Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin Warns of Federal Data Misuse at IOP Forum

News

Woman Rescued from Freezing Charles River, Transported to Hospital with Serious Injuries

News

Harvard Researchers Develop New Technology to Map Neural Connections

Corso’s Prediction Signals Im-Penn-ding Doom

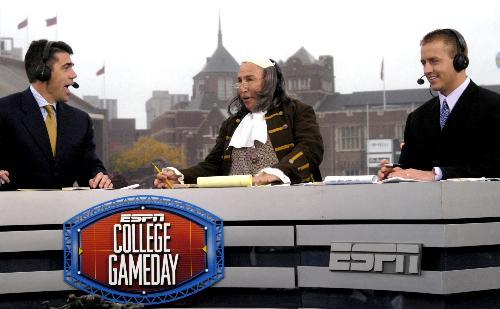

PHILADELPHIA—ESPN’s College GameDay co-host Lee Corso was set to don the costume of the mascot of the team he predicted was going to win Saturday’s Harvard-Penn tilt, just like he does every week right before the end of the show.

The thousands of rowdy fans in Philadelphia’s Franklin Field, representing both schools, wanted to know: would Corso come out dressed like a Quaker? A Pilgrim? Would anybody be able to tell the difference?

Corso left no doubts as he obliged the home crowd and appeared in a Benjamin Franklin get-up, predicting that Penn would defeat the Crimson and win the Ivy title on its home turf. And while Corso’s costume may have technically been inaccurate—Franklin isn’t actually Penn’s mascot—its spirit was absolutely correct. Following the genius of its bespectacled founding father, Penn invented a new way to win in this rivalry—by blowout.

I mean, this game was close for, what, a quarter? Clearly somebody on the Quakers’ coaching staff missed the memo that despite Penn’s national ranking, home-field advantage and large margins of victory this season, they were supposed to play out another classic, down-to-the-wire Harvard-Penn game. Instead, Penn played the role of Mike Tyson to Harvard’s “Hurricane” Peter McNeeley—a much-hyped, quickly decided matchup.

It was remarkable how both offenses were quite similar in that the running games were unable to produce any meaningful yards. That meant the game came down to the marquee players—the Neil Rose-Carl Morris connection for Harvard, and the Mike Mitchell-Rob Milanese hookup for Penn. How the defenses would respond to these potentially explosive duos set the tone for the course of the game.

It became a battle between coaching staffs and the Quakers won.

First, Harvard tried to shake things up by not only lining up Morris at his traditional isolation wideout spot, but also putting him in the slot position with two other wide receivers, the intent being to create more traffic to confuse the Penn defense.

Neither plan worked.

The Quakers, determined not to let Morris burn them as he had in the past, covered the All-Ivy receiver with “two-and-a-half” defenders. One cornerback would play right up against Morris, another defensive back would line up five yards behind him and a safety would be called over if necessary to defend against the deep ball.

The result? Morris had his least productive game in two years. He caught just three passes for 16 yards—and one of those was a 12-yard reception.

If Morris had all those defensive backs on him, somebody from Harvard should have been open. And they were, but they met with limited success. Penn blitzed enough that it was hard to find any running backs open for short passes because they were busy blocking, and it also meant that Rose had to find guys quickly. Mostly, he found sophomore Rodney Byrnes—who, by the way, will be very, very good next year—and Byrnes had eight catches for 60 yards.

And as if that successful cover scheme didn’t give the Quakers enough of an advantage, Penn was able to bring pressure with just its front four lineman. The key turning point in the game—when Penn’s Chris Pennington returned a Rose fumble for a touchdown—was caused by a strong rush that even got around the Crimson’s dependable senior right tackle Jamil Soriano.

Harvard, for its part, was stymied by Penn’s speed on the turf. Milanese, a small guy at 5’10, 175 lbs., lined up in the slot, so he was very rarely covered by either of Harvard’s junior cornerbacks, Benny Butler and Chris Raftery. Instead, a rotation of linebackers covered Milanese short, and he was up against safeties deep.

Good plays in football are made by finding the holes in the defense and utilizing them before they close up. Mitchell and Milanese found those holes—usually in between the retreating linebackers and the oncoming safeties—and the quarterback, with pinpoint accuracy, hit Milanese nine times for 139 yards including a touchdown.

And of course, this went on for four quarters, an unbearable three and a half hours, before Penn finally handed Harvard its worst defeat in seven years, 44-9.

I didn’t see this disastrous loss coming at all—but maybe that’s because I hadn’t checked my Poor Richard’s Almanac.

—Staff writer Rahul Rohatgi can be reached at rohatgi@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.