News

Harvard Grad Union Agrees To Bargain Without Ground Rules

News

Harvard Chabad Petitions to Change City Zoning Laws

News

Kestenbaum Files Opposition to Harvard’s Request for Documents

News

Harvard Agrees to a 1-Year $6 Million PILOT Agreement With the City of Cambridge

News

HUA Election Will Feature No Referenda or Survey Questions

‘In Other Words’ a Feat of Cross-Lingual Storytelling

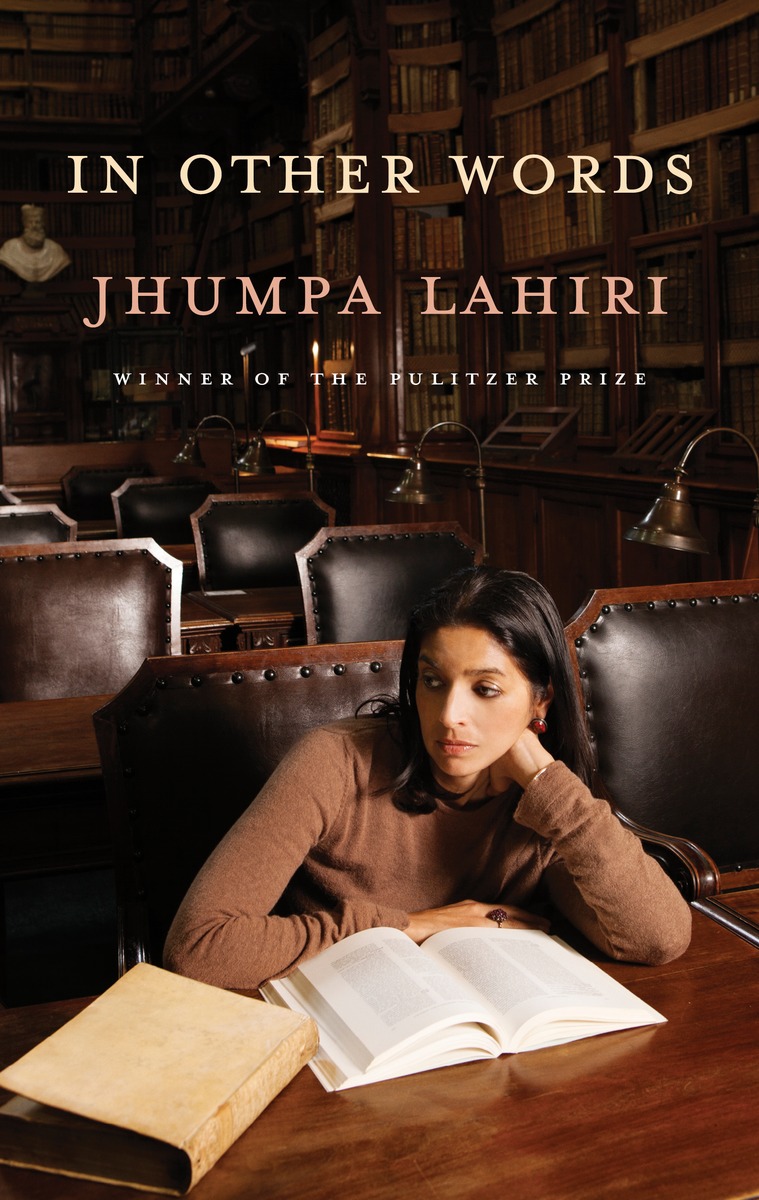

"In Other Words" by Jhumpa Lahiri (Knopf)

After publishing “The Lowland” to good reviews in 2013, acclaimed author Jhumpa Lahiri moved to Rome and stopped writing in English. “In Other Words,” her nonfiction debut, began as a diary in Italian. In the book, Lahiri’s original Italian writing remains on the left-hand side of each page spread, across from the English translation done by Ann Goldstein (translator for such eminent Italian authors as Elena Ferrante and Primo Levi). Twenty-three chapters—each of which could stand alone as an essay or story, and one of which, “Exile,” has already done so in “The New Yorker”—artfully and touchingly paint Lahiri’s journey into a new life, metaphorical descriptions of her relationship to Italian and English, the more technical aspects of her linguistic transition, and reflections on the role language plays in her life.

Lahiri’s resumé boasts a Pulitzer Prize, a seat on President Obama’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities, and a professorship at Princeton University, but she embraces her uncertainty in this second language. Explaining her choice not to translate the book herself, she writes: “I wanted the translation of ‘In altre parole’ to render my Italian honestly, without smoothing out its rough edges, without neutralizing its oddness, without manipulating its character.” The book is equally bold in its content. “In Other Words” deviates drastically from Lahiri’s bread-and-butter stories about first- and second-generation Bengali-American immigrants. The often suburban revelations of Lahiri’s prior fiction might induce déjà vu' or even boredom in dedicated readers, but this new, unexplored language offers a chance to freshly appreciate her unique sensitivity and quiet power. In her first entirely Italian short story, “The Exchange,” Lahiri writes: “She arrived as the season was changing. It was warm in the sun, cool in the shade.” There are no stunts, sleight-of-hand structures, or too-clever-by-half motifs. Such language—elegant, but sparse enough that the emotion beneath always carries—sounds familiar issuing from Lahiri’s pen, reminiscent of the works that elevated her to popularity some time ago.

Unlike in her fiction, however, Lahiri happily peels back the surface of language in her latest work, revealing its simple and graceful scaffolding. “Now I realize that I’m describing my relationship with Italian in another way, that I’ve introduced a new metaphor,” Lahiri confesses, in a chapter titled “The Hairy Adolescent,” in which she casts English as her hairy adolescent child and Italian as her baby. “Until now, the analogy had always been romantic: a falling in love. Now, as I translate myself, I feel like a mother of two children….” At various points throughout the book, Italian is also a lover, a lake, an ocean, a forest, an outfit, [Vcnice][SP], independence. English is a stepmother and a feral carnivore. Lahiri is the Greek nymph Daphne, transforming, via Italian, into a new self. At times, this deluge of metaphors begins to feel like inundation, and there are a few moments where the sentiments read too neatly, prompting a reaction not unlike how one would respond to a close friend’s cheesy pun. Writing about her struggle to distinguish between the simple and imperfect past tense, Lahiri explains: “Needless to say, this obstacle makes me feel, in fact, very imperfect. Although it’s frustrating, it seems fated. I identify with the imperfect because a sense of imperfection has marked my life...The more I feel imperfect, the more I feel alive.” But the driving wisdom beneath, no matter how many times one has heard it before, always rings true. Each metaphor is apt, and the genre does not demand that Lahiri restrain herself. Her joy in simply working with language emanates from every page, making every chapter and all its abundant metaphors a pleasure to read.

The uncomplicated frankness of Lahiri’s voice allows her to cover a satisfyingly wide range of subjects. She expresses and reframes familiar sentiments about the nature of love, both romantic and maternal, through the lens of her relationship to Italian and offers fascinating peeks into her world. She fishes in the Roman air and in Italian dictionaries for elusive adjectives, analyzes her own stories, and struggles with her newfound stylistic inelegance. In some of the book’s most poignant moments, she confronts such topics as her neuroses about writing, even in English; her conflicted feelings toward Bengali and English and the way in which they muddle her heritage and sense of identity; and the feelings of displacement that her linguistic and geographical nomadism inevitably create. These last revelations tactfully alternate with more biographical and language-learning focused chapters, so that overall, the book never feels too densely confessional—even while it resonates with haunting vulnerability.

As a milestone in Lahiri’s career, “In Other Words” embodies a tremendous feat: the relinquishment of the mastery and comfort of the old, and the complete, unsparing immersion in the new. As a feat of writing, “In Other Words” transcends its status as an individual’s historical document, becoming a manuscript about what it means to love and create. “From the creative point of view,” Lahiri notes, “there is nothing so dangerous as security.” In what felt to her like a dangerous leap of faith, she lets her insights stand naked and alone, garbed in neither character nor plot—and all the more beautiful and true for their lovely guilelessness.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.