News

Nearly 200 Harvard Affiliates Rally on Widener Steps To Protest Arrest of Columbia Student

News

CPS Will Increase Staffing At Schools Receiving Kennedy-Longfellow Students

News

‘Feels Like Christmas’: Freshmen Revel in Annual Housing Day Festivities

News

Susan Wolf Delivers 2025 Mala Soloman Kamm Lecture in Ethics

News

Harvard Law School Students Pass Referendum Urging University To Divest From Israel

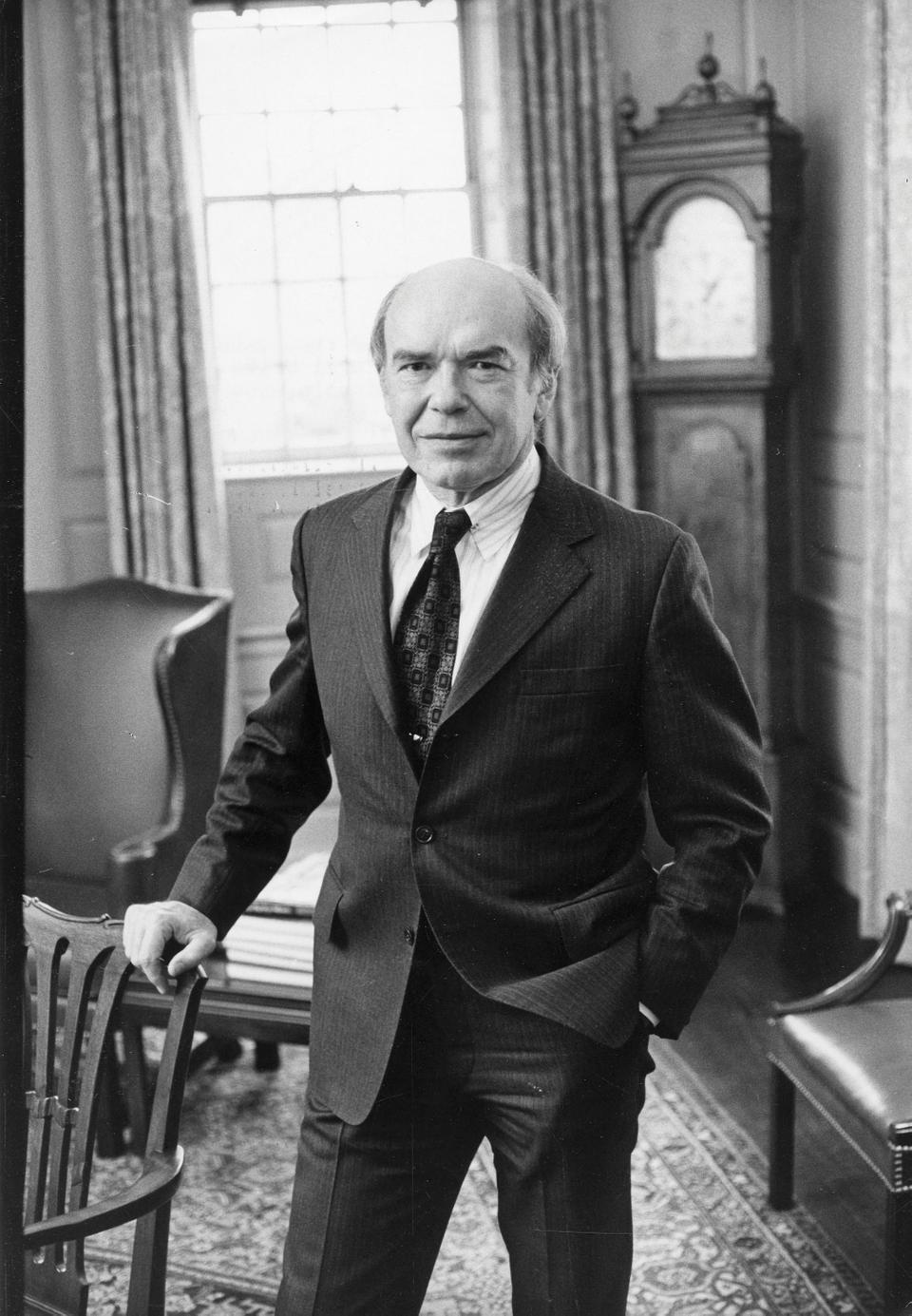

Former Brown University President Passes Away

Donald F. Hornig ’40 advised presidents, led Brown University through turbulent years of protest, and helped to design and then detonate the first atomic bomb. But his former colleagues at Harvard remember him as someone who helped to form generations of scientists and fostered a spirit of collaboration.

“Some professors have huge egos, and they really want to be remembered for the discoveries they made,” Harvard School of Public Health professor Joseph D. Brain said. “But I think Don was really unusual—perhaps because he’d already accomplished so much [and] that he came without ego and without agenda.”

Hornig died Jan. 21 at a nursing home in Providence, R.I. He was 92 years old.

Hornig was only in his twenties and a newly-minted Ph.D. in chemistry when his boss at the Underwater Explosives Laboratory at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute offered him an invitation to join a team of scientists working on a top-secret government project.

Upon his acceptance, Hornig unknowingly walked into the history books. The team was based at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, and the project was the now-famed Manhattan Project, where Hornig designed the explosive lens used to detonate the first atomic bomb in the summer of 1945. He was the last team member to inspect the bomb before pulling the trigger.

Until his death, Hornig maintained that the bomb had saved lives.

After the project disbanded, Hornig began a more traditional career in academia, teaching at Princeton and then at Brown. But his academic ambitions were derailed in 1963 when his Harvard classmate President John F. Kennedy ’40 asked him to serve as presidential science adviser. Hornig stayed in the post until 1969.

Hornig was in the midst of completing a six-year term on the Harvard Board of Overseers in 1970 when Brown University asked him to be its next president. His six year tenure from 1970 to 1976 was marked by much controversy, including student protests over the Vietnam War and university budget cuts.

Shortly after resigning at Brown, Hornig returned to Harvard as a professor and adviser, and later served as chair of the Department of Environmental Health and Physiology from 1988 to 1990.

After more than a half-decade of scrutiny at Brown, Harvard was a relief for Hornig, Brain said. Hornig was able to think creatively and collaboratively, and ultimately founded the Interdisciplinary Programs in Health, bringing the top minds in science to work on interdisciplinary public and environmental health issues.

“It was very telling to me that he came back to the School of Public Health and really saw public health and environmental health as a place where he really wanted to leave his mark as he approached the end of his career after all the opportunities and experiences he had,” said Douglas W. Dockery, chair of the Department of Environmental Health and Physiology at HSPH.

Hornig was the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including Guggenheim and Fulbright fellowships. He was also one of the youngest members ever elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

Hornig is survived by his wife Lilli, a Harvard-trained chemist and also a member of the Los Alamos team. After working to develop the bomb, she became a member of the Brown faculty and championed women’s rights.

—Staff writer Nicholas P. Fandos can be reached at nicholasfandos@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Most Read

- Harvard Suspends Research Partnership With Birzeit University in the West Bank

- 2 Years After Affirmative Action Ruling, Harvard Admits Class of 2029 Without Releasing Data

- Give the Land Up — Or Shut Up

- More Than 600 Harvard Faculty Urge Governing Boards To Resist Demands From Trump

- Harvard Students Don’t Need To Work Harder. Administrators Do.