News

Harvard Grad Union Agrees To Bargain Without Ground Rules

News

Harvard Chabad Petitions to Change City Zoning Laws

News

Kestenbaum Files Opposition to Harvard’s Request for Documents

News

Harvard Agrees to a 1-Year $6 Million PILOT Agreement With the City of Cambridge

News

HUA Election Will Feature No Referenda or Survey Questions

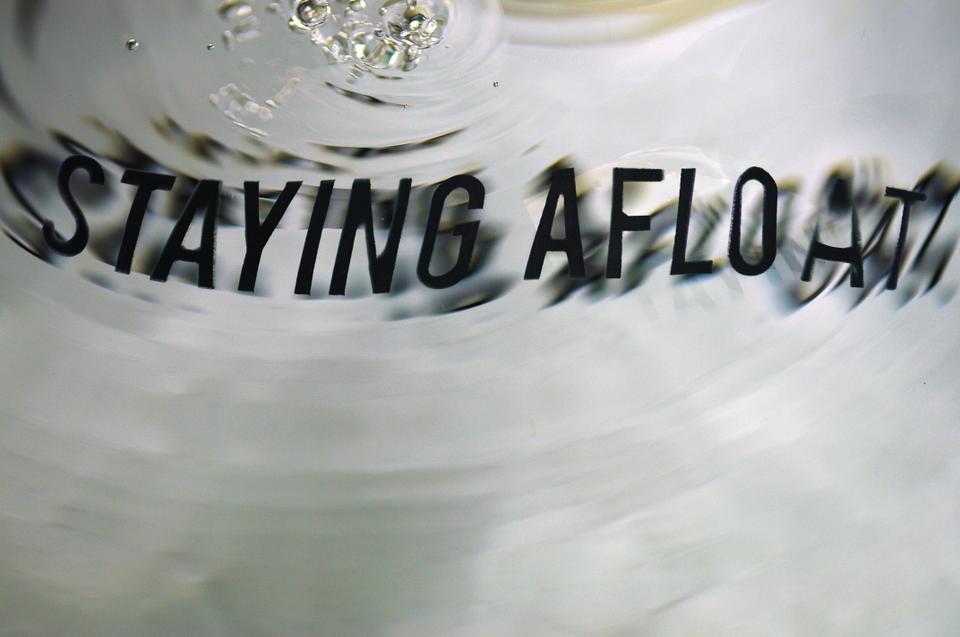

Staying Afloat

The University balances higher expenses with reduced budgets in the long wake of the 2008 financial crisis

The 2008-09 academic year kicked off in the midst of exceptional growth: The campus had expanded with the successful construction of Northwest Laboratories only a year before, and school budgets were quickly growing to accommodate more faculty.

But just a few weeks after students returned to campus from their summer vacations, the American markets crashed. And as stock prices slipped, so did Harvard’s endowment. Between the University’s direct holdings of financial securities and assets managed by external financial institutions, the endowment dropped by nearly 30 percent, tumbling from $36.9 billion down to $26 billion.

Fast forward to today. The University is approaching the end of its 2012 fiscal year. Saddled with reduced income from a still-depressed endowment, the University is currently managing increased budget responsibilities while wading through the continued ripples of the financial crisis that struck nearly four years ago.

“We have a smaller endowment and larger obligations,” University President Drew G. Faust said. “Those are very real challenges for us.”

A TEAR IN THE HULL

As Harvard’s endowment posted losses of nearly 30 percent in late 2008 and early 2009, deans and department administrators scrambled to cut budgets. Across the University, 275 workers were laid off, and hundreds were given reduced work hours. According to Wayne M. Langley, higher education director for Service Employees International Union Local 615, which represents many service employees at Harvard and other institutions in New England, unionized service workers at the University lost on average five hours of work per week.

“That may not seem like a lot,” said Langley. “But for people who are low-income workers, that makes a big difference.”

Harvard was trying to trim as much as it could. In order to pay for their budgets, schools in the University collect incomes from the endowment, annual donations, federal funding, and student tuitions. Normally, this revenue covers the total expenses of each of the schools.

But 2008 was not a normal year. As the University’s endowment tanked, donations, net tuitions, and other sources of incomes slowed to a drip, too. But by the time the market collapsed, the Harvard Corporation, the highest governing body of the University, had already approved the University’s budget through June 2009.

Pressed by reduced income to pay for their annual expenses, schools cut budgets to varying degrees.

BAILING THE WATER OUT

Starting in the winter of 2008-09, the Business School turned down the thermostat a few degrees at night to save at the margins. Administrators encouraged community members to shut down their computers at the end of the day and installed new, energy-efficient windows. But even as the financial outlook for the University has improved, the Business School has not gone back to its old habits.

“We thought to ourselves at the end of the recession, ‘Do we keep this in place?’” Business School Chief Financial Officer Richard P. Melnick said.

Administrators have appreciated the new challenge of paring their respective budgets, enjoying the new efficiency the focus has granted the departments. Most of these tune-ups are here to stay, even as the University recoups its endowment’s value and respective distribution increases.

“All of those kinds of scrutiny and efficiencies that came out of questions we asked in the wake of the downturn—we will continue,” Faust said.

For example, administrators and staff members at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs realized they could cope with fewer workers. According to Patrick McVay, director of finance for the Weatherhead Center, several staff members were leaving or retiring as the center was searching for ways to trim its budget. Now a few years out, the center has not refilled those positions.

“We’ve never returned to our previous staffing levels,” McVay said. “People sort of come together and you kind of muddle through, and you learn to do things that other people used to do. And I think we did that pretty well.”

Even across the river in Boston, at its offices on the 16th floor of the Boston’s Federal Reserve Building, the Harvard Management Company has rebooted its investment strategies. HMC, which manages the University’s endowment, has placed an increased preference on liquidity, thereby boosting Harvard’s access to quick cash. This access to greater liquidity, HMC President and CEO Jane L. Mendillo said, will allow the University to manage risk better.

RIGHTING THE SHIP

This September will mark four years since the financial crisis shook the American markets and dragged Harvard’s endowment down. In that time, Harvard has recovered $6 billion from the $11 billion loss that the endowment weathered. But some schools are just emerging from recovery mode.

Ali S. Asani ’77, chair of the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, recently won approval for two faculty searches. And this fall, after initial slowdown because of the limited available resources, Asani was even able to collect resources from the Faculty of Arts and Sciences to establish a new Modern Middle Eastern Studies concentration track.

“Things seem to be easing up,” Asani said.

FAS Dean for Administration and Finance Leslie A. Kirwan projected that the FAS deficit would likely be closed by the end of Fiscal Year 2012, this June 30. “The good news is that we’re slightly less endowment-dependent than at the beginning of the crisis,” Kirwan said.

This upswing is not just at FAS. Administrators at the Divinity School and the Law School said that their respective schools have proliferated in numnber of programs. At the Business School, faculty levels this year will likely increase to their pre-2008 number.

But for workers, the mood is still gloomy. Jerome J. Leslie was laid off from his job as web content manager in the Division of Medical Sciences at the Medical School in July 2009. Even though he was the only person in the office laid off, Leslie said that after the financial crisis, the workplace environment changed.

“No one really felt safe,” said Leslie, who was re-hired in October, just a few months after being laid off, by the Harvard Press Office.

The recent trend in staffing is, overall, positive, according to Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers Director Bill Jaeger, who said that 150 of the approximately 250 HUCTW jobs lost in 2008-09 have returned.

“I think, over time, the staffing levels are going to come back,” he said.

Jaeger pointed to growth-oriented initiatives, such as the House renewal project and a new plan for Allston, as signs that the University is getting over the effects of the recession.

“The University is on the way back and is entering growth mode again,” he said.

SAILING ON

As Faust said, the challenge of paying for more with less has not yet disappeared. Even as some schools begin to show improvement, volatile capital markets at home and abroad have led some administrators to admit that it might be some time before Harvard’s endowment returns to its pre-2008 levels. “A world in which our revenues are more constrained than our costs is likely in the near future,” Kirwan said. “There’s a lot of natural growth in expenses, but little natural growth in revenues.”

Kirwan said that FAS had cast a hopeful eye toward the University’s impending capital campaign for paying off some current debt. The current fiscal year seems like it will be a modest one for HMC’s annual returns. The S&P 500, an index of the 500 most valuable publicly traded companies, has stayed roughly flat from the start of the 2012 fiscal year, July 1, through the middle of May. And Harvard is still trying to manage the additional burden from the 2008 financial crisis.

“We are still feeling the effects,” Faust said. “We will be feeling the effects for a very long time to come.”

—Staff writer Samuel Y. Weinstock can be reached at sweinstock@college.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

From Our Advertisers

Over 300+ courses at prestigious colleges and universities in the US and UK are at your disposal.

Where you should have gotten your protein since 1998.

Serve as a proctor for Harvard Summer School (HSS) students, either in the Secondary School Program (SSP), General Program (GP), or Pre-College Program.

With an increasingly competitive Law School admissions process, it's important to understand what makes an applicant stand out.

Welcome to your one-stop gifting destination for men and women—it's like your neighborhood holiday shop, but way cooler.

HUSL seeks to create and empower a community of students who are seeking pathways into the Sports Business Industry.