News

News Flash: Memory Shop and Anime Zakka to Open in Harvard Square

News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

Painting a New Path at the Kennedy School

Of the more than 60 figures portrayed in the art of Annenberg Hall, three are women—two of whom are tending to children, while the third welcomes her warrior husband home to a life of domestic tranquility.

The pattern is replicated throughout Harvard—of the approximately 750 oil paintings that hang throughout the campus, about 690 of them feature white males. From marble busts to stained glass, Harvard’s art collection is stunningly grand and yet remarkably homogenous.

However, the long reign of this patriarchal portraiture may now be in jeopardy, thanks to the efforts of a professor determined to shake up the composition of Harvard’s male-dominated collection.

Jane J. Mansbridge, who has been a professor at the Kennedy School since 1996, is intimately familiar with issues of gender disparity at the Kennedy School, and has been a staunch advocate for women over the years through groups such as the Women and Public Policy Program at HKS. Mansbridge will serve as president of the American Political Science Association this coming year, which is among the highest honors in her profession.

But more recently, she has spearheaded a movement to add female faces to Harvard’s extensive art collection.

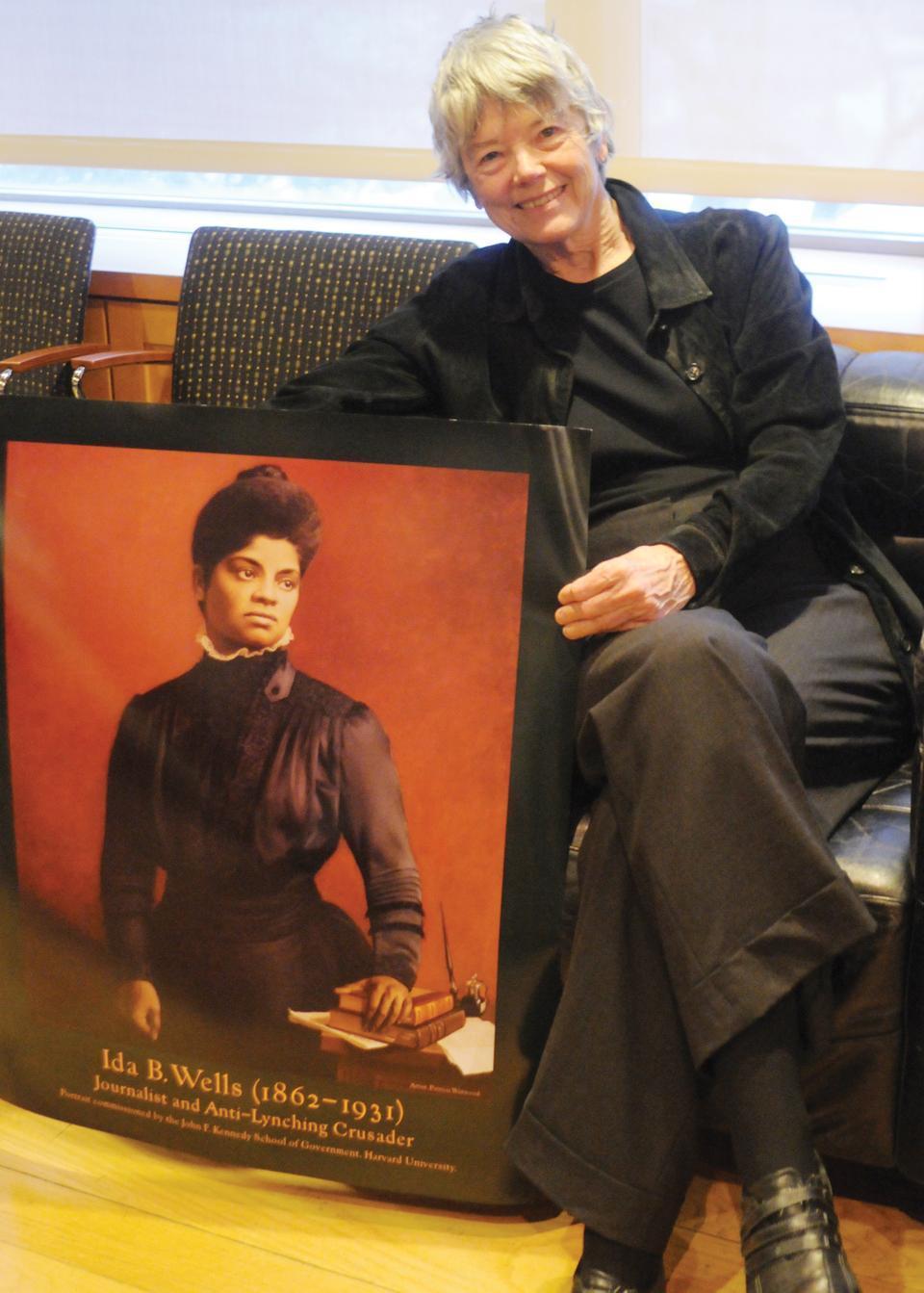

Because of Mansbridge’s elbow grease, a portrait of Ida B. Wells—an African-American journalist and early civil rights activist—now hangs in the Fainsod Room at the Kennedy School.

The portrait was commissioned in 2006 and cost $20,000. Then-president Lawrence H. Summers approved the request to use the president’s fund to cover the expense.

“Things like portraits on a wall can have real effects on people’s behavior,” says Mansbridge. “John Bargh and other psychologists of automaticity show these effects can be unconscious—if you’re in a room where all the portraits are of white males, you’re being primed to think that white males run everything.”

At the Kennedy School in particular, the gender imbalance among the faculty has been extreme for some time. Women make up just 19 percent of the senior faculty and 27 percent of the junior faculty at HKS, according to the 2011 annual report by Office of Faculty Development and Diversity.

While initiatives such as WAPPP have encouraged female students to seek careers in politics and public service, the gender ratio of the faculty is indicative of deeply ingrained inequalities that have historically kept women out of both government and portrait halls alike.

In conjunction with Mansbridge’s presidency of APSA, and the increased emphasis on gender equality and education at the Kennedy School, the timely addition of these portraits marks a step toward healing the gender rift that has plagued women in politics for so long.

POWERFUL PIGMENTS

When painter Stephen E. Coit ’71 read a Harvard Gazette article in 2003 announcing the allocation of funds for new portraits, he jumped at the chance to contribute to the diversification of Harvard’s collection.

Since 2003, Coit has painted over a dozen portraits of underrepresented leaders throughout history.

“When I was in Lowell House back in the late sixties, diversity was whether a portrait showed one hand or two,” says Coit.

Coit notes the significance of the portrait of Rulan C. Pian, a former professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations and Music, that now hangs in Cabot House. “It makes a strong statement to anyone who sees it, which is that she was a woman of Asian heritage, and that she made a contribution to Harvard,” Coit says.

The portrait of Pian was the result of an initiative launched in 2002 by S. Allen Counter, director of the Harvard Foundation. The Harvard Foundation received $100,000 from Summers to fund its Minority Portraiture Project, which commissions portraits of underrepresented members of the Harvard community. Former Dean Archie C. Epps III and former Director of the Bureau of Study Counsel Kiyo Morimoto are among those that Coit has painted.

While the Harvard Foundation has focused on diversifying portraiture more generally, Mansbridge has focused her efforts on the inclusion of women.

In addition to Ida B. Wells, Mansbridge has overseen the commissioning of a portrait of Abigail Adams. A potential portrait of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the president of Liberia and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, is being discussed. Sirleaf received a Masters of Public Administration from the Kennedy School in 1971 and served as last year’s commencement speaker.

Mansbridge says that at times it has been difficult to secure funding for the project. Because the Kennedy School has fewer discretionary funds than other schools, Mansbridge has had to rely on the president’s fund and the Women’s Leadership Board of the Kennedy School.

“Students from the Kennedy School go out and try to make the world a better place, which is not always a lucrative thing to do, so money for these projects can be tight,” says Mansbridge.

RECASTING GENDER ROLES

The obvious lack of women in Harvard’s art is largely paralleled in the makeup of its current faculty.

Part of the gender imbalance is due to the fact that women have long been deterred from entering fields that are perceived as more “masculine” than others, according to Mansbridge.

For example, international relations is an area that has long been dominated by men. But just as Harvard’s walls are being shaken up by women, so is the field of international diplomacy.

“International affairs are no longer just state to state, and diplomacy is no longer just men in ties sitting around mahogany tables,” says Cathryn A. Clüver, executive director of the Future of Diplomacy Project at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

In her tenure as president of APSA, Mansbridge said she hopes to redefine and diversify disciplines such as international relations and political economy—a field where all 10 tenured HKS faculty members are men.

“If you define international relations in the old way—when it was thought of as ‘bombs and bullets’—you’re going to get a predominantly male field of applicants,” says Mansbridge. “But if you open it up and make it more about human rights, you’re going to attract more women.”

Nicole Carter Quinn, associate director for finance and administration at the WAPPP, says that the art initiative plays a critical role in both recognizing the values of women leaders and broadening attitudes about women in traditionally male-dominated sectors of politics.

“Jenny [Mansbridge] is someone who really embodies the mission of the Kennedy School, which is ‘ask what you can do,’” says Quinn. “She’s worked tirelessly to make change and get some deserving women on our walls.”

THE OBSTACLES OF TRADITION

While issues of perception are part of the problem, recruitment presents an even bigger challenge.

Constructing a recruitment process that does not favor men in any way is much easier said than done. But as HKS becomes more aware of the complex factors that define applicant pools, it has adapted its mechanisms for fighting gender imbalance accordingly.

“Faculty selection processes should always be meritocratic, but it’s hard to do it right,” says Iris Bohnet, academic dean of the Kennedy School and director of the WAPPP.

Bohnet describes the need for “gender equality nudges,” such as hiring in bunches rather than sequentially, that lead to more effective consideration of employee diversity. She points out that no process is perfect, but that collecting more data will ultimately allow the school to refine its practices to assemble a more balanced faculty.

“Quantitative research will teach us how to close these gaps,” Bohnet says.

Mansbridge emphasized the importance of using objective metrics to ensure an even playing field.

“We know from the research that women do quite well in meritocratic processes, provided they’re not discriminated against for having children,” says Mansbridge.

Word-of-mouth recruitment methods often lead to the exclusion of marginalized groups, she says. “We have to make sure the channels are open in more than just old-boy network ways.”

For instance, Mansbridge says she supports reaching out to the military, which is famously meritocratic, as a way to draw women into fields in which it is often difficult to find female candidates.

“The challenge is working out a structured way of casting a broader net, and we have not yet figured out a way to do that very well,” says Mansbridge.

THE ART EFFECT

The nitty-gritty of recruitment aside, the new portraits of women have been most impactful in their psychological effects on the community and its institutional memory.

“These portraits are about changing the images of success that we have in our head, given the history that we have,” says Bohnet.

The portraits have also served as a source of inspiration to the current generation of up-and-coming politicians.

“This project is really exciting,” says Jenny Ye ’13, president of the Institute of Politics. “At Harvard we see portraits everywhere, and for women it’s encouraging to see that leadership is a lot more diverse than what’s hanging on the walls.”

Perhaps the most poignant product of this new portraiture is an oil painting of former professor Edith M. Stokey, who passed away this past January. Considered the “founding mother” of HKS, Stokey was a trailblazer for women at the Kennedy School and left behind a legacy of compassion and public service.

Her portrait, unveiled in 2008, now hands outside the office of the Dean.

“Portraits should try to say something inspiring to future generations,” says Coit. “That’s the point of all of this, and that’s what we’re trying to accomplish through art.”

—Staff writer Ethan G. Loewi can be reached at ethanloewi@college.harvard.edu.

This article has been revised to reflect the following corrections:

CORRECTION: March 8

An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified Nicole Carter Quinn as a former student of Jane J. Mansbridge. In fact, Quinn has not taken a class taught by Mansbridge.

CORRECTION: March 9

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the portrait of Ida B. Wells installed in the Fainsod Room at the Kennedy School cost $10,000. In fact, it cost $20,000.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Most Read

- Harvard Outsourced Its Slavery Research. Then a Former Employee Began Notifying Descendants — Without Its Knowledge.

- Harvard Built the Biotech Industry in Cambridge, Then Let It Go. Now It Wants Back In.

- At Rally in Harvard Square, Protesters Accuse Harvard of Complicity With Trump

- Harvard Kennedy School Revokes Fellowship to Human Rights Activist, Saying Offer Was Premature

- 6 Harvard Students, Recent Grads Have Visa Status Restored