Making Change

Ten years ago, Harold A. Moore was sleeping on the streets of Boston. Today, he has a red motor scooter, a college degree, and his own apartment.

Ellen “Helen John” E. Cromarty’s struggles with mental and physical health problems have resulted in homelessness on several occasions since her illness began 36 years ago. Employed and housed today, she gives change to homeless people she passes as she glides down the street in her motorized wheelchair. When she can’t afford to hand out coins, she carries sandwiches to distribute.

Poor business decisions compelled Shawn Lawrence to close his computer repair shop and take up construction work; then an on-the-job injury forced him out of work and onto the streets. Today, he is living in transitional housing and looking forward to renting an apartment and completing a degree in computer science.

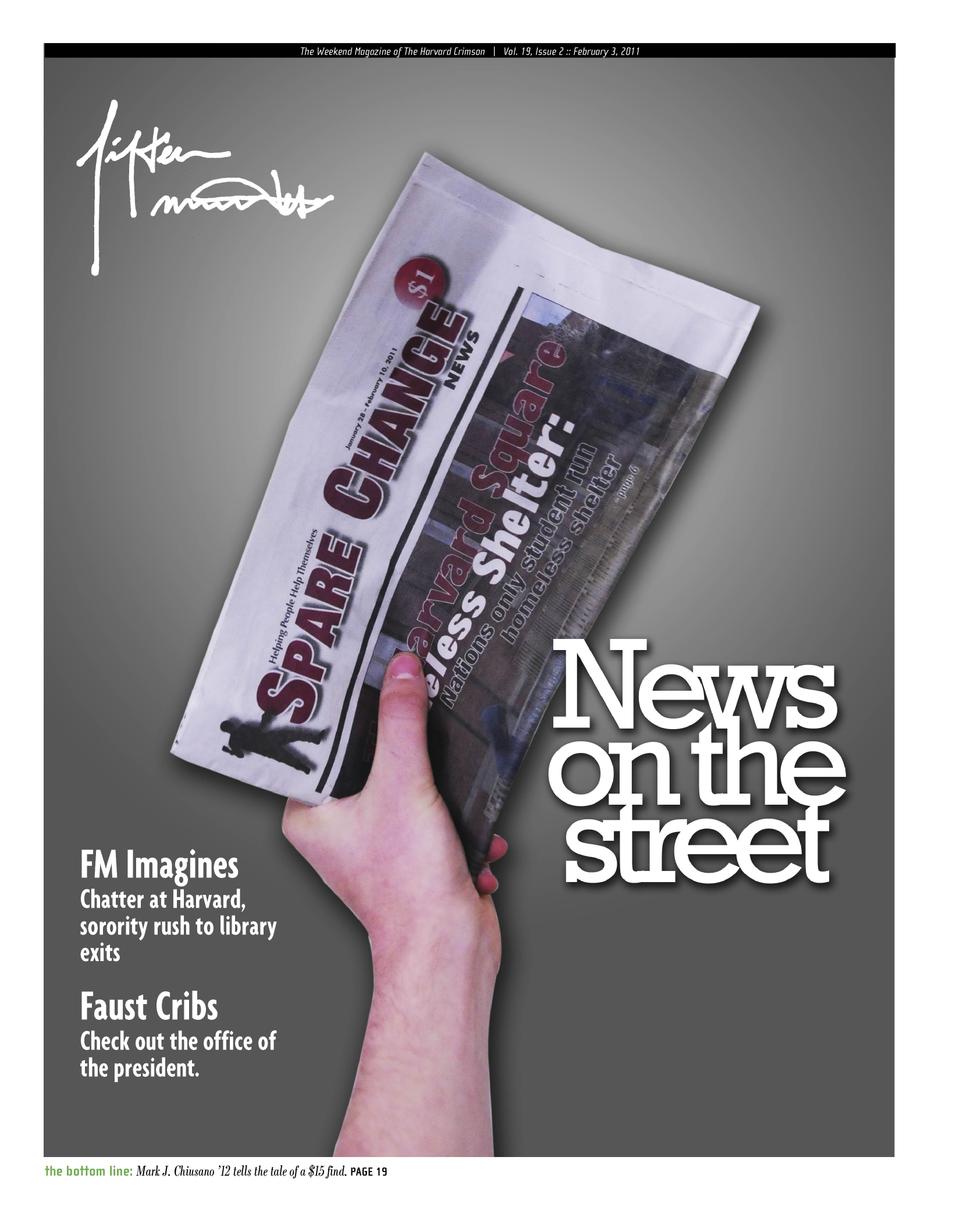

Through Spare Change News, a biweekly Boston newspaper, these individuals and others like them have the chance to voice their stories. For many men and women—such as Moore, Cromarty, and Lawrence, all of whom make their livings by selling this newspaper on the streets—Spare Change itself becomes a meaningful new chapter in their narratives.

BY, FOR, AND ABOUT THE HOMELESS

Spare Change News bills itself as a “newspaper with a conscience.” The publication contains articles on topics affecting the homeless, poetry and artwork submitted by people living on the streets, and a listing of support services available to homeless people in the Boston area. The writers are drawn from two different pools—college students, who typically write for free, and Spare Change’s homeless and formerly homeless vendors, who receive a $50 payment for each piece they contribute.

Each Spare Change News vendor buys copies of the newspaper for 25 cents per issue and then sells them on the street for one dollar. Most vendors buy at least 50 papers each week; some of the top sellers hawk upwards of 300 papers weekly. All together, the corps of vendors sells 8,500 papers each week.

“It just goes to show that stereotypes—that the homeless are lazy, that they don’t want to work, that they’re all addicts—aren’t always true,” says Editor-in-Chief Adam J. Sennott. “Our vendors work tirelessly. I don’t know how they do it, rain or shine.”

STARTING FROM SCRATCH

Spare Change News was born in 1992, the brainchild of Tim Hobson, a homeless man, and Timothy Harris, a housed member of Boston Jobs with Peace. Hobson recruited about a dozen other homeless people whom he met at the Harvard Square Homeless Shelter, including James L. Shearer.

“I thought he was insane,” Shearer recalls. “How are we going to write and produce this thing when we all live in the shelter?”

Yet, inspired by the example of street papers in New York City and London, Spare Change’s eager founders unified around the idea and resolved to take their publication one step further: while the other papers were written by volunteers and then given to homeless people to sell, according to Shearer, the founders of Spare Change dreamed that theirs would be written as well as distributed by the homeless.

They met every day at the McDonald’s in Central Square, sometimes riding the T for hours to keep warm while they planned their project. After about seven months, the first issue rolled off the presses at The Crimson, which printed the paper for its first two years.

Within the first year, all of the founding members had earned enough money to get off the streets—and more than 60 additional people had signed up to become vendors. Shearer left the paper for other employment in 1994, then returned as a vendor in 2003. Two years later, he took over as the president of the organization’s board of trustees.

This January, Shearer, still the board’s president, returned to selling the paper two to three days each week. Due to “relationship issues,” he says, “I got in a situation where I might be facing homelessness again.” He insists, “It’s not a bad thing” and says that he is happy to be selling papers again at his former post in Brookline.

“This is my old corner. People remember me,” he says. “I missed it.”

WORK IN PROGRESS

Housed in the basement of Harvard Square’s Old Cambridge Baptist Church, Spare Change News’ main office is a cluttered room holding two computers (“When we can get new ones, we’re probably going to donate these to the Smithsonian,” Sennott says ruefully, gesturing at the bulky machines), a few rolling chairs, a bookshelf, and the hustle and bustle typical of any newsroom in the world.

Robert Sondak, a Spare Change vendor and one of the paper’s most frequent writers, strides into the office, fresh from an event he was covering.

“I interviewed five volunteers and the manager,” he reports.

Sennott quizzes him on the details of the event, then hits a snag. “You didn’t get any of their last names?” he repeats. His face registers the thought processes of a trained editor: mild disappointment, quick evaluation of options, and mental reshaping of the story flash across his youthful features. “We’ll just quote the manager heavily then,” he tells the writer matter-of-factly. Sondak agrees.

“I don’t consider myself a professional writer,” Sondak says in a conversation two months later—then reveals that he has written over 50 articles for Spare Change, one for nearly every issue of the paper that has come out since he started writing.

Sondak is an old hat at this, but “not every writer is at the same level as others,” says Sennott. While he tries to impart an editor’s guidance, he says he also strives to leave the writers’ unique styles intact.

“One thing Spare Change prides itself on is providing a voice for people,” Sennott says. “They each have their own kind of shock value. It’s amazing what people have been through ... there are so many different reasons people are on the street.”

There were 7,681 homeless men, women, and children counted in the 2008-2009 Homeless Census in Boston—an 11 percent uptick from 2007 to 2008. This is the community that Spare Change’s vendors know. “Our vendors have expertise about facets of society that mainstream society typically doesn’t see,” says Executive Director David J. Jefferson. “We try to be a catalyst through which mainstream society can learn about these human stories.”

SHELTER TO SCHOLAR

Moore has made his living entirely from selling Spare Change News for the past 10 years. When he embarked on his career as a vendor, he was sleeping on the streets, staying in shelters only during the coldest weeks of the year. He manages to sound nonchalant as he discusses his years of homelessness. “It wasn’t too bad,” he says, perched on his red Honda scooter as he sells his wares outside Shaw’s grocery store in Porter Square. “But by then I got sick and tired of the shelter. After selling the paper for a couple years, I got myself a bed.”

After a stint in that bed, which was a Single Room Occupancy unit at a YMCA, Moore purchased a van which he lived in temporarily, retaining his Y membership to use the facilities. Shortly thereafter, he decided to return to Newbury College to finish the degree that he had begun as an 18-year-old, nearly 30 years earlier. He sold the van, rented an apartment, and hit the books.

“For five years, I was working 30, 35 hours a week [selling Spare Change News], and another 20 going to class,” he recalls. “I was getting up at seven—and not getting home until 11 two nights a week. It didn’t seem like I never took a day off.”

One of Moore’s regular customers, who passed him in the Porter Square T station every morning, noticed his exhausting schedule. Concerned for his favorite paper vendor, this man took up a collection at his workplace and presented Moore with over $200 last Christmas, telling him to use it to take a vacation.

Instead, Moore put the money toward paying his expenses when he was unable to work for four months due to a debilitating foot condition. Today, his feet are on the mend—he’s walking again, though he relies on crutches—and he hopes to take that vacation sometime soon.

“I’ll get away for two to three days,” he says. “It’s going to be someplace warm. I haven’t been to too many places. Las Vegas, Miami, something like that.”

As his costs rise—he predicts that he will soon need to move farther from Boston as rent on his current apartment creeps higher—Moore says he will soon look to use his new college degree to get a different job, but he hopes to continue to sell Spare Change part-time.

A PRACTICED SALESMAN

Across the same parking lot, another vendor, Algia L. Benjamin, softly sings “Spare Change Newspaper,” as passersby head into CVS.

“I think I’ve made like four dollars today,” he grumbles. He says he sells “20, maybe 30” papers in a typical day, and this week—it’s just past Thanksgiving the first time I talk to him—Benjamin says that his intake “is really supposed to be better.” The Christmas spirit isn’t brightening today’s sales, though.

A woman bundled in a swank coat glances up from the ground when Benjamin croons the name of the paper.

“No, I’m sorry, I don’t,” she mutters. “At least she spoke,” he comments.

“A lot of people walking past tend to ignore you,” says Benjamin, who has been selling the paper since the year it was founded. “Even when you speak in a clear tone, they still pretend they don’t hear you.”

Things pick up a bit, though; in the next 45 minutes, one woman, who Benjamin says is a regular customer, buys a paper, and two more hand him a dollar but decline to take the news

paper. In the same amount of time earlier that morning, Moore made no transactions.

A few years ago, Benjamin attended the North American Street Newspaper Association’s annual conference where he met with representatives from the 30 other street papers in the organization. The highlight for Benjamin was the opportunity to travel to the event, which was held in San Francisco. “I’d never been there before,” he says. “I got to see the Golden Gate Bridge.”

As an early vendor and longtime staunch supporter, Benjamin is proud of the difference that Spare Change News has made in vendors’ lives. He numbers himself as one of the most profoundly affected by the project.

Talking about his sadness today when he passes panhandlers, Benjamin says, “I used to be like that. I’d sit on a crate with a sign. No sir, I don’t want to be out there—drunk all the time, drugged out. It’s not a good feeling.”

I ask how he overcame that time in his life, and he answers instantly: “Spare Change News.”

Now, he talks about his hopes for starting his own “non-profit landscaping business,” which will employ needy people to do yard work at low cost for elderly customers. He’s consulted businessmen for advice, and he plans to apply for a grant to get the project rolling.

Yet his troubled past is never far from his mind. “I just know I never want to be homeless again,” he says. “Like a lot of people are one paycheck away from homelessness—if I get sick and can’t work I’ll be back there. I have to make sure I eat right, dress right when we’re out here when it snows. It could be hailing and we’d be out here.”

He has just returned from visiting his parents, who moved from Boston to Florida in 1978 after a record-breaking blizzard hit New England. Even though he spends five to six hours outdoors selling the paper each day, Benjamin says he doesn’t want to relocate to a warmer climate like his parents.

“I think about it,” he acknowledges. “But my daughter’s here, and it’s not right for me to move .... If I could get [the girl’s mother] to move to Florida, I’d move. I’d go wherever she’s at.”

Benjamin and his daughter’s mom split up several years ago, but he and 10-year-old Jessica are still close. Sometimes, she comes to work with him. She helps him promote his wares—“People tend to buy the paper when you have a kid with you”—and he splits the day’s profits with her.

VETERAN ON THE STREETS

It’s a cold but sunny Saturday morning on Newbury Street, and Boston’s ritziest shopping district is still largely asleep. With a cup half-full of change and an orange plastic crate to sit on, however, Michael W. Wingate is already open for business.

Wingate’s story is the reverse of Benjamin’s and Moore’s: rather than coming to Spare Change homeless and securing housing through his earnings, Wingate has gone from sleeping in his own apartment to a shelter since he began selling Spare Change News in August.

A native of Alabama and an army veteran, Wingate moved to Boston with the assistance of the Veterans’ Association. The price of living in the city on just his Social Security Disability Insurance benefits was steep. Paying his rent became more difficult when his grandmother died and he began sending part of his monthly checks to his family to help them make ends meet. Considering panhandling but wary of asking for money outright, he befriended a group of experienced beggars who congregated at a Burger King. There, he learned about Spare Change News.

He began to buy papers, 20 at a time. On a good day, he says, he sells all 20; other days, he only makes eight sales.

The extra income was not enough to pay the rent on his apartment. Since November, he’s been sleeping in Boston’s Long Island Shelter. Five days a week, he sits on his crate in front of Dunkin’ Donuts. Usually, he’s selling Spare Change; when he does not have money to buy the 25-cent papers, he seeks donations from passersby. “Some days I use the money to buy me some food,” he explains. “Then I have to wait a few days and shake the cup to get up some money to go buy the papers.”

On Mondays and Wednesdays, he takes the day off to travel to Brockton, a multi-bus journey that takes him from 4 a.m. to 9 a.m. to complete. He makes the arduous trip, he says, “for love.”

His girlfriend lives there, along with their 22-month-old daughter. Wingate, 52, sees his young daughter as frequently as he can—in part because he is still mindful of his other child whom he does not get to visit, a son now four years older than his own 30-year-old current girlfriend.

At age 17, Wingate engaged in a high school romance with a 16-year-old classmate. “We fooled around,” he says. “She ended up pregnant.” Feeling compelled to “be an honorable man,” Wingate joined the army in order to support his son.

He saw the child only once, when he traveled from his station in Fort Benning, Ga, to visit the baby and his girlfriend—and found that she had become involved with another man in his absence. All these years later, he still thinks about going to Cleveland, where he recently learned that the woman lives: “just kicking the door in and saying, ‘Where’s my boy?’”

He notes immediately that he would need money to finance such a trip, however, and every night in the shelter reminds him that he is not in a position to travel. At Long Island, Wingate says he encounters “crazy folks screaming and hollering like a mental institution.”

As if to illustrate his point, a person comes toward us. Wingate counsels me not to make eye contact with the person when they begin shouting into the nearly empty street.

The person is “partial to E&J,” Wingate says. He catches my blank look and clarifies, “Brandy.”

In his time at Long Island, Wingate says that he has witnessed drug use, even though shelter rules ban controlled substances. “They shoot dope there; they’re smoking crack. They’re selling five-dollar pints of liquor,” he says. “You see people naked in the bathroom looking for little white specks on the floor. Everybody thinks they dropped some.”

Wingate is no stranger to drugs. He was arrested in 1990 for cocaine distribution and spent seven years in prison. His youngest brother is serving a life sentence for fatally shooting a 15-year-old during a drug transaction gone tragically wrong.

“I put all that behind me,” Wingate says. “I constantly think about how I went wrong so I don’t go wrong again.”

Since he was imprisoned, he says, “I savor life a little bit more now. I enjoy the people. I don’t worry about money much.”

“I get my blessings from God,” he says. Even if “home” is a homeless shelter, “I go home with 10 to 13 dollars, and that’s enough for me. I ain’t greedy.”

He is generous enough to share his small fortune with the birds. He walks into Dunkin’ Donuts and purchases a bagel, which he crumbles into pieces and sprinkles on the sidewalk. “Come on, chilluns,” he coos approvingly, as the birds of Back Bay flutter down in front of him.

PROBLEMS IN THE PROCESS

These vendors have cultivated the trust of loyal customers. Not all, however, are so scrupulous.

Spare Change has been plagued by vendors who attempt to charge more than one dollar for the paper, claiming that the money is a donation to some nonexistent charitable fund.

Jefferson acknowledges that “even though it’s against our policies, there are some vendors out there who will have a nip [of alcohol] before they go out to sell.”

To address these problems, Spare Change gives badges to its approved vendors and prints a warning to customers on the front page advising them to buy the paper only from vendors sporting the fuschia tags.

WIELDING THE RED PEN

As editor-in-chief, Sennott hears stories like Wingate’s, Benjamin’s, and Moore’s every day—and helps them make it to press. It was stories like these that led him to Spare Change News in the first place.

Two years after dropping out of high school at age 16, Sennott decided that he wanted an education after all. He enrolled in an adult education program. Three years after he achieved his GED, Sennott was a junior at Bunker Hill Community College aspiring to become a sportswriter when he happened to walk past a Spare Change News vendor. Aspiring to write, he contacted the paper. His first piece was published, and the editor asked him to write another one. And another. And another.

By the time he graduated, Sennott had covered a multitude of topics for Spare Change News: a 93-year-old woman who has opened her home to nearly 100 foster children in her lifetime; a bill protecting homeless people from hate crimes which passed Maryland’s legislature but failed in Massachusetts; a book club for the homeless which meets regularly on the street. (When Sennott visited, they were reading O. Henry; he was surprised to learn that one of the members was a Yale graduate. “He had a degree in philosophy. That might have contributed to it,” Sennott smirks.)

At the time that Sennott graduated from college last June, the position of editor-in-chief had just opened up at Spare Change News. Though he is again applying to universities, including Harvard, and he still hopes to find a job in sportswriting someday, he’s happy in the editor’s desk for the moment.

“If the Celtics win another championship, it doesn’t really matter,” he says. “These stories that we publish really affect people’s lives. Someday when I’m a sports journalist, I’ll get to write useless stories, and that will be fun.”

PLANNING AHEAD, REVISITING ROOTS

Right now, Spare Change needs funds to continue telling its stories.

In 2008, the paper found itself on shaky financial ground. The newspaper draws the majority of its operating budget from donations, not paper sales, and everyone was giving less as the economy tanked. The cancellation of a major annual gift—The Crimson reported in 2008 that the donor, a member of the Buffett family, had formerly contributed $40,000 per year to Spare Change—left the paper’s leaders unsure whether it could survive.

“For a moment there, we didn’t think we were going to make it,” recalls Shearer. He and dozens of other dedicated vendors and volunteers redoubled their fundraising efforts. “This is something that we really can’t let go by the wayside,” Shearer says. “It gives people a voice; it gives people hope. It’s helped thousands of people get off the streets.”

So far, Spare Change has held on, mainly through appeals to individual donors. “Things have turned around to a degree,” says Jefferson. “Our funding is not nearly as secure as it ought to be. We’re okay for the next several months.”

Yet Shearer is optimistic. He hopes that following the paper’s 20th birthday, which it will celebrate in 2012, Spare Change will even be secure enough to increase publication to weekly rather than biweekly.

Shearer mentions that Harvard could help Spare Change meet that goal. “It’s our neighbor,” he says. The Spare Change office is located just down the street from Mr. Bartley’s and the Kong, and longtime vendor Gregory H. Daugherty’s booming sales pitch to each “young man” and “pretty lady” who walk through Harvard Square has been a fixture of undergraduates’ experiences for more than 15 years.

Shearer briefly refers to a $10,000 grant which Spare Change received in 2008 from a Harvard Business School student-run foundation, but he then enumerates what he considers more extensive involvement from other nearby universities. Suffolk University sends numerous students and faculty to volunteer; a lab at MIT has recently partnered with Spare Change to create online profiles for several vendors; and college students from throughout the region write for the paper, though Sennott says he has yet to have a writer from Harvard.

“I wish Harvard was a little bit more involved,” says Shearer. “We’d welcome them with open arms.”

For now, Shearer is concentrating on refocusing the paper on its original purpose. Before his tenure as president, he says that the organization came under the leadership of “your basic suit-and-tie crowd, Starbucks crowd, do-gooders” who neglected to focus the paper on homeless peoples’ views.

Benjamin complains that some of the stories that Sennott and Jefferson are most excited about—interviews with Governor Deval L. Patrick ’78 and nine-time Olympic gold medalist Carl Lewis, for example—do not directly voice the experiences of people on the street. “This is not the Boston Globe or the Herald. This is Spare Change, a homeless newspaper,” he says.

The current leaders are committed to keeping homeless perspectives central to Spare Change. Sennott proudly announces that an average of five to six vendors have been contributing to each issue recently, pointing out a cartoon drawn by a homeless veteran that adorns the back cover of the current issue.

Shearer shares this vision as well: “I want to get it back to low-income individuals running the entire operation,” he says.

KEEPING PERSPECTIVE

That original concept still holds a prominent place on the wall of Jefferson’s office, where a framed copy of the first issue announces, “Welcome to Our World.”

In the makeshift newsroom across the hallway, Sennott keeps another piece of Spare Change memorabilia tacked to the wall, a computer print-out in a plastic frame. It’s a quote from historian and Cambridge resident Howard Zinn: “Spare Change to me is an extraordinary illustration of what homeless people can do, because they can reach out to the public and say, ‘Here we are, and we’re intelligent and sensitive people. We’re poets; we’re writers. We’ll tell you what caused our situation and we’ll ask you to do something about it.’”