News

News Flash: Memory Shop and Anime Zakka to Open in Harvard Square

News

Harvard Researchers Develop AI-Driven Framework To Study Social Interactions, A Step Forward for Autism Research

News

Harvard Innovation Labs Announces 25 President’s Innovation Challenge Finalists

News

Graduate Student Council To Vote on Meeting Attendance Policy

News

Pop Hits and Politics: At Yardfest, Students Dance to Bedingfield and a Student Band Condemns Trump

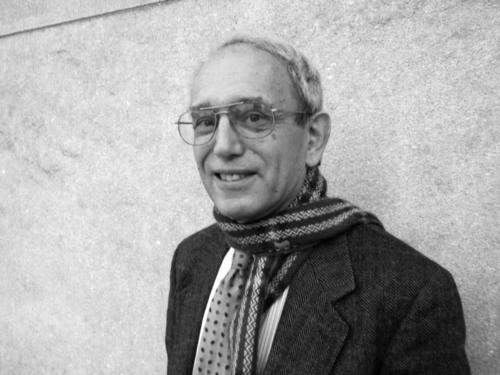

Stephen A. Marglin

Radical Harvard economics professor defies ‘established order’ of the 1950s

In 1972 he was arrested at an anti-war protest. He has been called a Marxist and a radical. But in 1968 Stephen A. Marglin ’59 was one of the youngest professors to ever be granted tenure. Today, he is the last of a dying breed—the radical Harvard economics professor.

On the Harvard campus and within the economics faculty, Marglin emerged as a prominent leftist economist with the publishing of his seminal critique of neoclassical economics, “What Do Bosses Do?”, and by pushing for an alternative to Social Analysis 10, or Ec 10, that would present competing views to orthodox economics.

But Marglin, who has even challenged the assumptions of capitalism as too Western-centric and critiqued its hierarchical nature, emerged from anything but a radical time and place—late 1950s Harvard.

Marglin describes the Harvard of his undergraduate years as a place that accepted the “established order” and was unwilling to contemplate its de facto all-white, gender segregated character—a place dominated by the children of elite prep schools and suffused with Cold War politics.

At a dinner for national honors society Phi Beta Kappa graduates at the Signet Society, an official from the Eisenhower administration had been recruited to give the after-dinner speech. He addressed the importance of the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways as a crucial component of national defense.

Marglin said he stood up to ask a question.

“Why does everything we do for a good reason have to be in the name of defense?”

According to Marglin, the official was taken aback.

Though the remarks may have presaged his later stances, Marglin hardly emerged from Harvard a radical—at graduation he was a neoclassical economist, concerned with the optimization of limited resources and, as such, apolitical.

As an undergraduate, Marglin was not a cafe-dwelling, revolutionary intellectual; rather, he was a Jewish public school kid from California who worried about looking like and fitting in with East Coast private school kids.

In those days, the schools of thought that ushered in 60s radicalism and Marglin’s own left-ward turn—feminism, the anti-nuclear and anti-war movements, and the sexual revolution—were nascent as ideologies.

Students at Harvard during the late 50s consistently said that political engagement on campus was virtually nonexistent, with students expressing more concern over the closing of the popular bar Cronin’s to make room for the Holyoke Center than the absence of black students on campus, male-female segregation, or lingering anti-Semitism.

But Marglin would make a drastic departure from the depoliticized environment of the late 50s to marry his economics with a radical brand of politics.

A self-avowed “pink-diaper,” Marglin said his left-wing politics stemmed from his parents—moderate leftists in their own right.

But not until a research trip to India in the mid 60s, did Marglin politicize his economics. Marglin said that his so-called radicalization was a gradual progression that lacked definite turning points.

But in India, Marglin came as close as he ever would to such a moment.

Teaching math-savvy Indian grad students basic macroeconomics, Marglin found his students nonplussed by the economic theory despite their deep understanding of the mathematics. That realization in India propelled Marglin towards a leftist economic career that would challenge the Western-centric assumptions behind orthodox economic theory.

Not until Marglin left Harvard did he accomplish this leftward turn. The Harvard of his undergraduate years, he said, would never have allowed it.

“There was a powerlessness in the exact sense that there was an established order and one had to live with it,” Marglin said. “It was a powerlessness that we could live with because we were all privileged.”

—Staff writer Elias J. Groll can be reached at egroll@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Most Read

- White House Officials Say They Sent Harvard April 11 Demands in Error, New York Times Reports

- Hour by Hour: How Harvard’s Donations Surged After Garber Challenged Trump

- No, Harvard’s Endowment Cannot Withstand Trump

- As Garber Stands Against Trump, Money From Harvard Donors Pours In

- Harvard Will Fight Trump’s Demands